At the time of this story, an estimated 26 swans had died at Lake Eola Park, raising questions amongst residents about their care and the quality of their habitat. In our investigation of the recent avian flu outbreak, Orlando Shine was approached by a volunteer with a long list of complaints concerning the city’s governance of the urban lake and its resident population of swans. The following is a summary of what we discovered.

Our investigation is still ongoing, but it includes:

- City officials received early warning signs of a possible outbreak in mid-December, including reports from a volunteer docent, but multiple swan deaths were initially handled without necropsies or formal documentation, which delayed their response.

- Internal communications suggest concerns about staff exposure to avian flu during prior outbreaks, though the city disputes that any cases were officially confirmed.

- Lake Eola functions as a downtown stormwater basin, meaning swans are being kept in water that routinely receives polluted runoff, contributing to poor water quality and chronic health stress.

- An independent water quality expert weighs in to say the lake is impaired by excess nutrients, is likely overpopulated with swans relative to its size, and may be subject to management practices that compound long-term ecological stress.

The City manages roughly 60-80 swans at the downtown lake, comprising five species: Royal Mute, Whooper, Black Neck, Australian Black, and Trumpeter swans, in a sort of open-air aviary that has been part of the lake’s identity for over 100 years. We’ve lost over a third of the population due to the recent outbreak.

The City of Orlando carried out a necropsy of the first birds to die to assess the cause of death, and publicly confirmed on January 5 that it was avian influenza. This is not a new risk, as Lake Eola experienced a bird flu outbreak in February 2024, when roughly 15 swans died, and similar outbreaks have occurred in pods across North America.

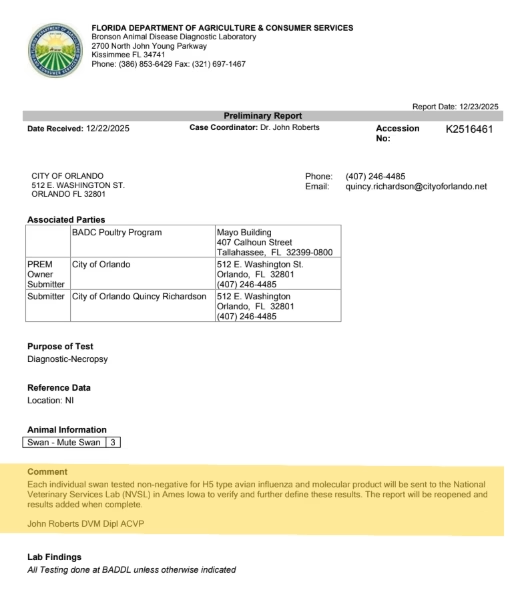

Swans were first submitted for a necropsy ahead of Christmas, with the results of “non-negative” being made available to the City of Orlando on December 23, as seen in the correspondence provided below. The status “non-negative” is a technical lab term that indicates the presumptive presence of the virus, but requires further testing for final confirmation, and is seen as a preliminary positive result.

On December 29, City of Orlando Commissioner Patty Sheehan held a press conference at Lake Eola to say they were waiting on necropsy results from the other swans that had just died.

During an outbreak, most city governments will pressure wash walkways, sanitize gathering spots, and remove public feeders to reduce virus spread via droppings, but usually let herd immunity handle it, in the hopes that the ones left will better handle the next wave of infections that come.

The City of Orlando did the same, per the recommendation of the Florida Fish and Wildlife (FWC) and advice of local experts, and then posted public notices (in English only) for park-goers to keep their distance from birds and avoid contact with any excrement so as not to be exposed to the virus. Or, as Sheehan also shared in the above press conference, “Don’t eat poop.”

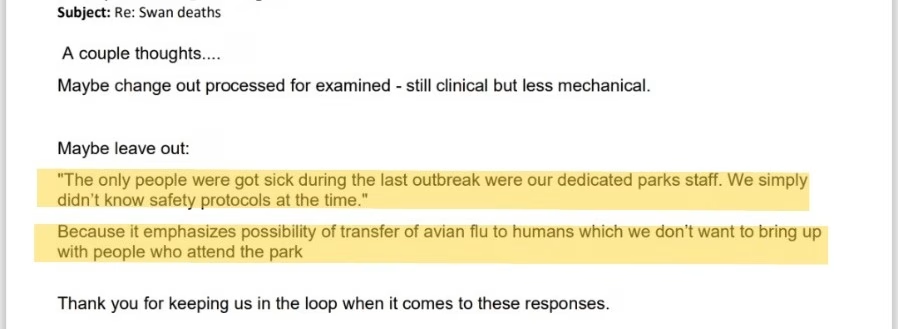

Advice that parks staff may have benefitted from back in 2024, as it appears some members of City staff may have been exposed to avian influenza at that time. In an email between Sheehan and the head of the Parks Department and City Hall communications teams, a staff member advised the omission of a line citing possible previous staff illnesses in order to avoid complications with people visiting the park during the holidays.

According to the CDC, while people rarely get bird flu, when they do, it’s because of close, unprotected exposure to infected animals without wearing respiratory or eye protection, something Sheehan alludes to in her omitted statement when she shares, “We simply didn’t know safety protocols at the time.” The CDC states that there has been no person-to-person spread of the virus identified in the United States.

When we asked the City’s public information officer how many staff members may have contracted avian flu during the last outbreak, they responded, “We have no confirmed cases of staff contracting the avian flu.” When pressed that we had an email that suggested otherwise, they responded with the following:

In our role as Public Information Manager, our responsibility is to provide accurate, verified, and official information. Email conversations among staff do not constitute official statements, nor can they be treated as such without proper verification.

The information you are referencing that Commissioner Sheehan may have been told has yet to be verified. In an effort to remain diligent and ensure the information we provide is accurate, staff are continuing to review whether the information Commissioner Sheehan may have received can be substantiated.

At this time, the City was not notified that any staff contracted avian flu in 2024, nor is there documentation confirming that staff did so. For that reason, we would not communicate such information publicly without proper verification.

They later followed up to say, “We can confirm no one from staff were diagnosed with the avian flu.”

A senior staff person told Orlando Shine that roughly 500,000 people are thought to have visited Lake Eola Park during the holidays.

PREVENTION

While a vaccine for avian influenza does exist, the CDC does not allow its use for waterfowl. Over the holidays, the City started adding a supplement called Baicalin to the swan feed, though it is not really a cure and just helps to ease the symptoms, perhaps buying more time for the birds’ immune system to do their thing. Baicalin is a flavonoid extracted from Scutellaria baicalensis (Chinese skullcap) that has been used in Chinese medicine for thousands of years and is noted for its antiviral properties.

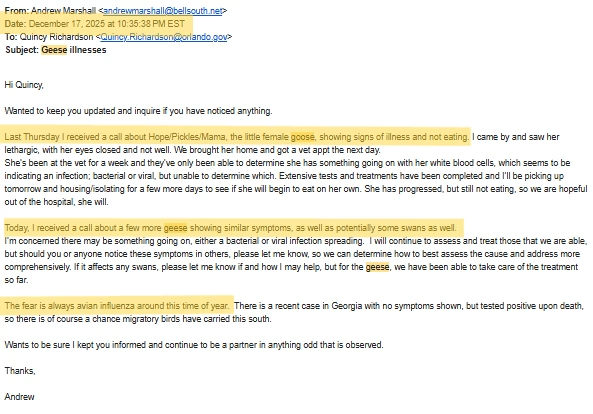

Although City representatives has stated that they acted as quickly as they could, despite holiday delays due to staff vacations, we have records that show a volunteer in the swan program, Andrew Marshall, had actually made city staff aware of a possible outbreak on December 17, 2025, almost a week after he had aided in the care of a resident goose at Lake Eola named Hope that was showing signs of illness and not eating.

As stated in Marshall’s email to park manager Quincy Richardson, the vet he hired nursed it back to health, but not before they got a call about a few more geese with similar symptoms, which they suspected was avian influenza. Richardson responded on December 18, 2025, saying that his staff had “…not observed any changes with the birds thus far. With all of the people in the park with the holiday decorations, I would be surprised if it is something that may be fed or left behind for them to eat. This time of year, we tend to see strange things/behavior, but struggle to find the cause. If we have any swan issues, I will be sure to let you know.”

That same day, a swan died, but was not submitted for a necropsy and was simply disposed of, according to Marshall. When a second swan died, it was also disposed of by City staff without a report or necropsy, prompting Marshall to ask if city staff had a standard operating procedure (SOP) they were supposed to be abiding by when they encountered a dead swan. Marshall says he was told they did not, and he created his own to help similar incidents from happening again.

We asked Director of Families, Parks and Recreation, Lisa Early, if there was an SOP for dealing with sick or deceased swans (in part because of Marshall’s account and also due to Sheehan’s omitted statement about staff possibly being exposed to the virus due to improper training), and she said, “Absolutely. It’s based on best practices in the field and advice from Dr. Geoffrey Gardner. And also we use Florida Fish and Wildlife and the Florida Department of Health.” We asked for a copy, but had not received it at the time of this post.

Dr. Gardner is a Lakeland-based veterinarian who is on-call with the City of Orlando to assist with the managed swan population at Lake Eola, and oversees the annual “swan roundup” each year, where he examines the birds for health issues, tracks their weight, and oversees minor procedures. Though not an avian specialist, he practiced as a general practitioner for 40 years prior to retirement. His father, Wade Gardner, was the official swan doctor for the City of Lakeland, and he followed in his father’s footsteps, caring for Lakeland’s swans for 25 years himself, and even volunteering for the Queen three times in an annual swan roundup.

“My special niche is swans. Which not too many people even bother with. Most people don’t want a bird that’s 30 pounds and can knock you down. I grew up taking care of swans. So, all of my childhood, I worked out of my dad’s office. I’ve been around swans as long as I can remember.”

Dr. Gardner’s advice to the City during this most recent outbreak has been to wait it out and build herd immunity, saying that once the migratory waterfowl leave Lake Eola in the spring, the flu will follow, hoping that the survivors will be better equipped to deal with the next strain that comes.

DESIGN CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

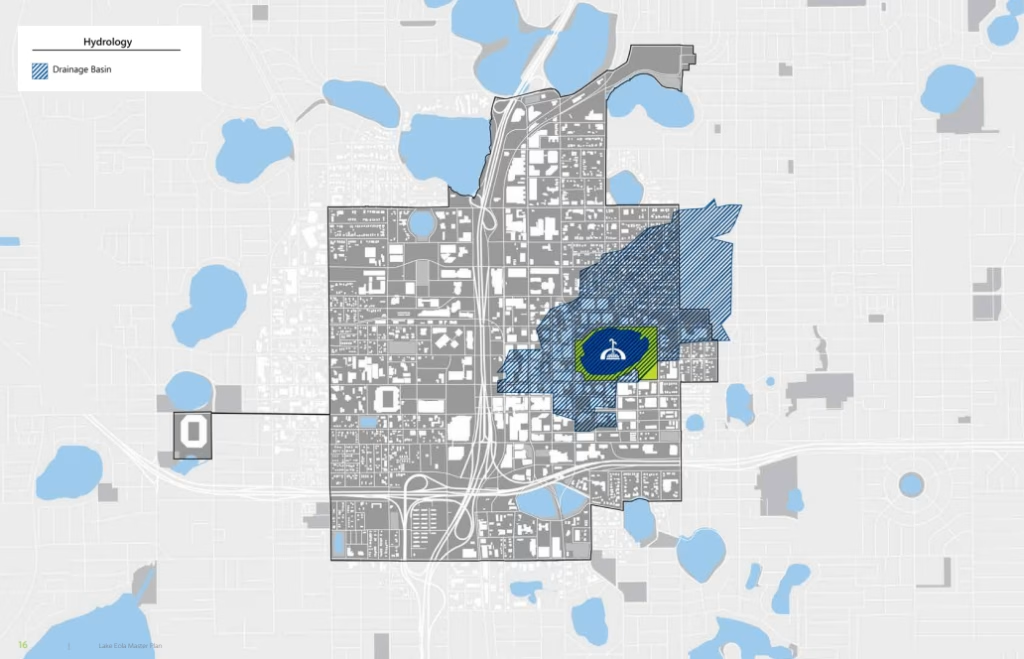

While City Hall and the Parks Department assure that staff are doing their best, the deaths have triggered public concern and renewed criticism of how the City of Orlando manages the lake and the swan program, including a recent petition demanding some changes from City Council. With the pending $60+ million renovation of the park on the horizon, the City has an opportunity to address a couple of design challenges: how to manage a population of high-profile birds being kept in an increasingly trafficked, iconic lake that also functions as a major downtown stormwater basin; and how to keep a healthy flock of birds in one place that is also accessible to wild birds that can expose them to outside illnesses, like bird flu.

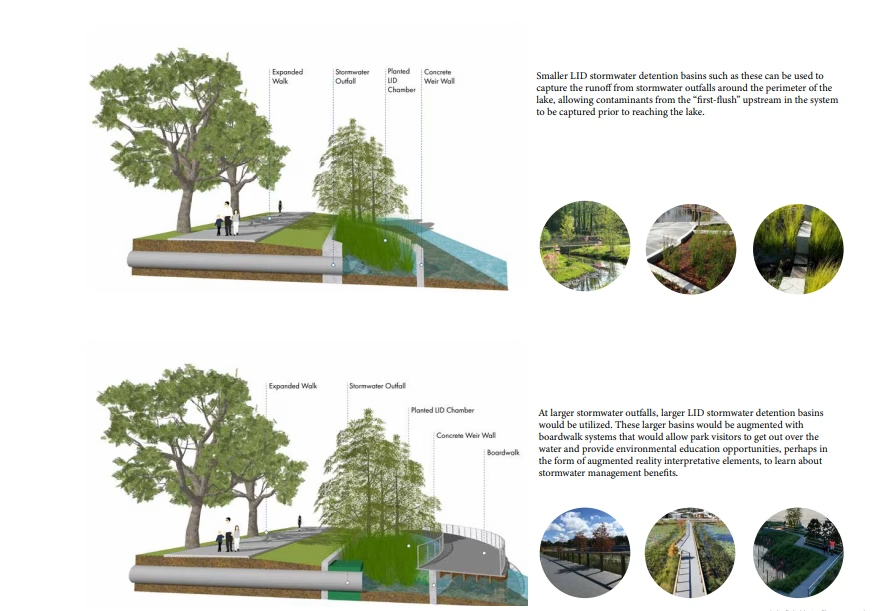

While the majority of the redesign plans currently look at projects that include widening sidewalks and upgrading the restrooms and amphitheater, the project is also meant to address the underlying environmental conditions that affect swan health, including water quality and pollution caused by stormwater runoff.

Lake Eola is the receptacle for a large percentage of downtown Orlando’s stormwater. That runoff carries pollutants off streets, sidewalks, and construction areas and into the water. The City is effectively trying to run a public-facing animal care program in water that is structurally exposed to pollution and contamination.

According to Public Works, the central focus of the Lake Eola Park Master Plan (Website) is to “improve overall water quality and habitat conditions, which directly benefits the health and quality of life of the city’s swans.” According to the City, key design elements in the plan currently include:

- Low Impact Development (LID) Retention Ponds: Ten LID retention ponds will be constructed to collect and naturally filter stormwater runoff before it enters Lake Eola. These ponds allow sediment, excess nutrients, heavy metals, and hydrocarbons to settle out of the water column, resulting in cleaner water gradually returning to the lake. They also increase on-site stormwater storage capacity, helping to reduce flooding.

- Storm Water Retention: A 12,000 SF rain garden will be installed and planted with native aquatic and semi-aquatic vegetation. These plants filter stormwater through natural biological processes, reducing sediment and nutrient loads before runoff reaches the lake.

According to Public Works, the City of Orlando has “coordinated with environmental and wildlife professionals, such as the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and veterinary experts who advise on avian health.” Though the vet on-call, Dr. Gardner, who fields the majority of the cases at Lake Eola, shared with Orlando Shine that he had not been involved in the process so far. We asked the City who the veterinary experts were who had contributed to the plan, but were directed to make a public records request, saying, “The plan is still in progress.” We hope to get those names at a later date.

The City of Orlando provides annual data from roughly 80 local lakes to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, which is available to the public via the Orange County Water Atlas website. We asked a professional consulting firm specializing in water quality and nutrient remediation to interpret the most recent water quality data for Lake Eola, HERE, so we could gain an overall understanding of the lake’s health. The consultant asked to remain anonymous in case working with us could negatively affect their work with local municipalities.

The consultant’s main findings were that a body of water the size of Lake Eola could likely only support a single breeding pair of swans in the wild, and that, according to the water quality report, the lake does not currently meet water quality standards to protect aquatic life. Read their full statement below.

“Under Florida’s water quality assessment program, the lake is designated as impaired for nutrients (TP and chl-a), meaning it does not currently meet water quality standards established to protect aquatic life and recreational uses.

Lake Eola’s impairment is consistent with conditions commonly observed in small urban lakes, where nutrient inputs from stormwater runoff, fertilizers, organic debris, and wildlife exceed what the lake can naturally assimilate. This is not unusual for small urban lakes…particularly those with little to no inflow or outflow. When a watershed is more than three times larger than the lake itself, as is the case for Lake Eola, nutrient loading often overwhelms the lake’s ability to maintain balanced water quality without active management.

In the wild, a breeding pair of mute swans (2 adult swans) needs 10-20 acres to survive. In the wild, a 28-acre lake would normally sustain one pair of swans, not dozens. Significantly higher numbers reflect artificial support (think additional feedings…and then therefore additional waste…meaning more nutrient pollution) and urban conditions, and they can negatively influence both water quality and bird health over time. Lake Eola is “overdosed” with swans, and their presence is likely contributing to water quality issues.

However, when I spoke with Dr. Gardner, and asked him his thoughts on the ideal carrying capacity of the lake for a group of swans, he said the sky is the limit.

“The concentration of the swans is pretty much a non-issue from the standpoint of the fact that they’re cared for. If they were just naturally foraging swans, and they had to care for themselves, there’s no way. They wouldn’t make it. They’d starve to death. They’re very much better off than, say, natural swans that may not have enough to eat. [Lake Eola] can support a lot. We had as many as 80-some brds at one point.”

I asked our expert what they thought of that and why those algae treatments would be allowed if they could adversely affect waterfowl on the lake, and here’s what they said.

Recurring algae growth in Lake Eola has probably led to repeated copper-based algaecide treatments, a common management response in urban lakes not under the jurisdiction of FWC. While copper treatments can temporarily reduce algae, they do not address the underlying nutrient sources driving algal growth. Over time, repeated copper applications can accumulate in sediments and may pose ecological and wildlife concerns, particularly for birds that forage in sediments or ingest grit (depending on the formulation used). In nutrient-rich systems, reliance on chemical algae control without reducing nutrient inputs can create a management cycle of recurring blooms, repeated treatments, and increasing stress on aquatic life.

The State prohibits the use of copper products in any waters that they permit/regulate – larger than 160 acres and having two or more owners of the shoreline)…but I suspect that since Eola is exempt from these regulations, that City staff are probably using copper in an effort to reduce algae concentrations.

Copper-based algaecides (such as copper sulfate or chelated copper) are commonly used to control algae in lakes and ponds. In birds, copper is generally poorly absorbed compared to fish or invertebrates, and healthy birds can regulate and excrete excess copper. When copper does accumulate, it is most often found in the liver, not throughout the body. Chronic exposure or overdosing – such as repeated treatments, use in small or shallow lakes, or treatment in low-alkalinity water (Eola is probably higher alk) – can lead to elevated liver copper, sometimes accompanied by liver damage (e.g., necrosis or bile duct changes). High copper levels on necropsy are rare and usually associated with direct ingestion or long-term exposure, not routine, well-managed treatments.

During an earlier conversation about overall swan health, Marshall had shared that at least one necropsy over the years had resulted in high amounts of copper, as indicated below, in a report for a swan that had died in November 2024. The verdict at that time was that copper toxicity simply contributed to the death of a bird that had already been suffering from an “underlying parasitic disease.”

City staff told us that they use GreenClean-branded liquid algaecide treatments at Lake Eola, as needed. The brand is a biodegradable alternative to copper sulphates. When pressed as to when they started using it, they said simply, “We started using that in 2025.”

WHO IS IN CHARGE OF THE SWANS?

The majority of the day-to-day care for the swans is leveraged by volunteers, led by a volunteer docent, Andrew Marshall. He’s been volunteering with the City of Orlando for the past five years, specifically with the swan program at Lake Eola, and has spent the last two years leading the City’s Swan Docent Program, but grew frustrated over the holidays when he felt City staff were slow to respond to the avian flu outbreak, saying there isn’t anyone who focuses solely on their care.

“There’s really nobody in charge of the program. Just the rangers and the park manager, and they do their best, but the last thing they want to do is look after the birds. There’s no person at the point of the program, and they’re under-resourced at the park.”

– ANDREW MARSHALL, SWAN PROGRAM DOCENT

Early confirmed with Orlando Shine that Lake Eola Park currently has nine full-time staff members and 26 seasonal employees carrying out a variety of different tasks, all led by a single park manager, Richardson, primarily focused on events and day-to-day operations. She also confirmed that there was no single employee responsible for the care of the swans, but it was rather a shared responsibility for all City departments.

The City does have a number of designated animal experts on the payroll, though, including an official City Beekeeper. Yet no designated Swan Keeper. When pressed as to the role of the Docent in the day-to-day care, though, things seemed to get a little sticky.

“The Docent program was originally started back in 2008. And the original idea was to actually make this an educational program for the public, to help people understand how swans live and give them tours, and understand how we take care of the swans here. We started doing the roundups around the same time, so the docents and volunteers would help organize the roundup and handle the logistics.” When asked why the park had come to lean on Marshall as a volunteer to do more than just event logistics, Early shared, “We’ve had other docents and volunteers who have been, perhaps, less involved, but this is his passion. So he’s, you know, constantly in touch and saying, ‘I can do this, I can do that, I can do the other.’ So it’s evolved based on his desire, willingness, and gumption to do those kinds of things. [We] don’t have a Docent Policy that clearly lays out that the volunteers are responsible for A, B, C, and D.”

Marshall, who leads a non-profit with his wife called Friends of a Feather (Website) that cares for the health needs of non-native waterfowl in and around downtown Orlando, grew frustrated with the City’s slow response to his updates on sick swans at the park, and took to social media to share their concerns.

The City of Orlando has made it clear over the past month that Marshall is a volunteer, and not an official spokesperson for the program. But he has indirectly been put in charge of looking after not just the other volunteers, but also coordinating vet visits with Dr. Gardner and the swans’ health records. Since there’s not really any one single person in charge of the program, there’s nobody there to make the lift and manage the minutiae, and it’s the basis for most of Marshall’s frustrations with the City of Orlando.

Marshall says he’s been trying for over a year and a half to connect with Early, to establish a Swan Advisory Board or something like it, to create a platform of experts and stakeholders to oversee the program. With no success in lining up a meeting or even a response to an email. We asked Early’s office what may be leading to the delay in response and received the following message.

While the City does not currently have a formal Swan Advisory Board, we do have a robust and established network of veterinary and wildlife professionals who actively advise and support our swan care program. The City works closely with Dr. Geoffrey Gardner, a licensed veterinarian who is on call and provides ongoing guidance on swan health, treatment, and welfare.

In addition, the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services provides access to a state laboratory that specializes in animal disease diagnostics and best practices for managing animal health concerns when they arise. We also coordinate closely with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC), which monitors and aggregates data related to avian influenza and other wildlife health issues and provides guidance consistent with state and federal wildlife standards.

Beyond these professional partnerships, the City values the role of its dedicated volunteer community. Volunteers work closely with staff and routinely share observations, feedback, and best practices, which are taken into consideration as part of the ongoing management of the swan care program.

At this time, we believe this collaborative and science-based approach ensures the highest level of care for the swans. However, the City remains open to continued dialogue and evaluating additional ways to strengthen communication and engagement around the program as appropriate.

In the meantime, things like the cost for new holding pens and feeding stations are falling to outside funders like Marshall himself or Sheehan, who has spent thousands of dollars over the years in support of the program.

“It’s [funding] mostly coming from Patty [Sheehan]’s discretionary fund. Sometimes, from the Park’s budget, if they put a charge on a credit card. But that’s for smaller emergency expenditures. The swans are a significant economic draw for the park and downtown Orlando, and the fact that there’s no real budget to care for them is crazy. There’s the Swan-A-Thon fund, of course. But those funds go into some sort of trust. There isn’t anything formal that makes sure it goes specifically into swan care.”

– ANDREW MARSHALL, SWAN PROGRAM DOCENT

Early shared that there is roughly $45,000 earmarked for the care of the swans in the Lake Eola park budget, but that a portion of that is also used to pay for Richardson’s salary. She estimated that it accounts for roughly six hours of Richardson’s salary each week.

The trust Marshall is referring to is The Orlando Community and Youth Trust (Website), a non-profit entity that manages the funds raised through the platform, via the City of Orlando’s Families, Parks and Recreation Department. The Trust also funnels funds for Orlando Kidz Zones, City-owned memorial benches, and the Dueling Dragons of Orlando boating initiative with Orlando law enforcement and local youth.

The [Swan-A-Thon] funds are used is often donor-directed. For example, donors may choose to sponsor the addition of a specific breed of swan to the park. In those cases, the Trust facilitates the purchase and delivery of the swans in coordination with the city. All expenditures are aligned with the overall goal of ensuring the health, care, and long-term wellbeing of Lake Eola’s swan population.

We filed an information request to see how much had been raised through the fund since the launch and how it had been allocated, but we had not received the information at the time of this post.

SWAN SONG FOR THE PROGRAM?

With Sheehan announcing her tenure as District 5 Commissioner is coming to an end in two years, and that she’s not seeking reelection, the state of the Swan-A-Thon fundraising success, the high price of purchasing a swan, and the growing likelihood of stronger and more frequent avian influenza incidents, some residents have started to question the long-term viability of the swan program, including News 6 anchor Steven “Trooper Steve” Montiero, who took to social media this week to share his thoughts.

Ending a swan program is not unusual. Cities typically do it when animal welfare, staff safety, disease risk, or operational costs no longer pencil out. Woodstock, Ontario, ended its swan program in 2024 after 12 years, citing concerns that included the health and safety of both the swans and city staff, stating, “…it just made more sense to stop fighting the inevitable.”

If Orlando chooses this route, it would likely mean relocating remaining swans to approved facilities or partner programs, reframing Lake Eola’s identity away from a curated swan attraction, and investing in planned water quality and habitat improvements anyway, but for a more naturalized lake ecosystem to highlight more native bird species like, ibis, anhingas, or even more showy roseate spoonbills and American flamingos.

Swans at Lake Eola has always been a choice, not a necessity. They were added to shape the image of the city, but as we grow, maybe that image is one without a swan at the heart of it, at least not one that isn’t living its best life.